Hora inglesa, “English time” in Portuguese, is a common jab at Western punctuality in Brazil. Because, in the world’s fifth-largest country by land mass, being on time to a party is uncool and uncouth. “The unspoken rule is that the host waits until the time the party is supposed to start, and only then begins to think about having a shower,” a translator explained in a BBC travel piece. ARPANET, one of the earliest computer networks, arrived in Brazil hora inglesa, in 1975.

Less than two years after ARPANET’s first international connections, Vint Cerf and Keith Uncapher demoed a connection to the network from São Paulo at the first Latin American Seminar on Data Communication. The party had officially started. But Brazil had every intention of being fashionably late.

It was a three-ring circus, orchestrating the South American country’s introduction to Western networks. The Brazilian government wanted to control the flow of information across borders, while academia championed unfettered access to international research, both of which were hampered by local telecoms that coveted monetization.

In the end, all it took to break the impasse was a few copper wires, laid across the Gulf of Mexico to a high-energy physics lab just outside of Chicago, in 1991.

The whole internet in your inbox

Email and messaging were, for both academics and hobbyists, the biggest motivation to connect to Western networks. “The physicists, for example, did their master’s and PhDs abroad, and wanted to maintain contact with researchers in other countries,” Brazilian Internet Hall of Fame inductee Demi Getschko remembers. “Outside Brazil, e-mail was already being used extensively, but we didn’t yet have it in Brazil. So then we began to research how to bring it here.”

B1726 machine via Classic Computer Brochures

Getschko, for his part, worked nights at the State of São Paulo Research Foundation (FAPESP), programming software to manage the foundation’s grants and research. Computer hardware was expensive, even before factoring in Brazil’s import restrictions. So, Getschko and his boss operated out of a house, alternating shifts to get the most out of their Burroughs 1726 machine.

“I would work there at night. I began going to the house on Pirajussara Street three times a week, turned on the Burroughs and tried to write some of the programs.” During one of his shifts, Getschko met Oscar Sala, one of the physicists who pined for email after studying in America. Sala was a FAPESP board member and friend of Fermilab.

As interest in networking grew both domestically and internationally, FAPESP moved its headquarters to a bigger building. “I still remember the day in which we moved the equipment from Pirajussara Street to the new headquarters. The B1726 was transported in a half-open truck. I went with it and prayed for it to not rain.” It would be several years before Getschko got the country connected to the internet, but the pace of progress was accelerating.

CIRANDA terminal screen via the Ciranda Project

Embratel, one of Brazil’s largest telecommunications companies, had launched a handful of point-to-point networks for private connections. CIRANDA was one of the most famous examples. It was a closed network reserved for Embratel employees, aptly named after a Brazilian dance that involves people holding hands in a circle, much like the digital communities that blossomed as it became easier to get a hold of modems and terminals.

Paulo Sérgio Pinto launched Brazil’s first BBS in 1984 with nothing more than a TRS-80, a manual-dialing modem, some experience programming in FORTRAN, and access to an Embratel network. BBSes, or bulletin board systems, let users connect to a host and exchange messages, share files, and post to discussion forums. Paulo would leave his computer open to host connections from 8pm to midnight during those first few months, answering dial-ins by hand every time he heard a modem call his line.

FidoNet logo via Wikimedia commons by Sabadomingo

While Paulo’s BBS was limited to users in-country, NGOs introduced access to international email with AlterNex in 1987. “This new entity was based, initially, on the bulletin board system, which allowed for the exchange of messages and chat. AlterNex operated via a single phone line that connected to a FidoNet node in the United States to exchange e-mail messages once a day.” With its directory of over 9,000 BBSes, Brazilians clamored for more network throughput.

The pre-Internet internet

Around the same time that AlterNex went live, Fermilab agreed to establish a dedicated connection with FAPESP. The plan was to name it SPAN (São Paulo Academic Network). NASA, it turned out, already had a network by the same name, so they scrambled it, and ANSP (Academic Network at São Paulo) was born.

Unbeknownst to Getschko and his team, an alphabet soup of other government and academic groups had been pursuing similar objectives in parallel. It wasn’t until Michael Stanton, another future Internet Hall of Fame inductee from Brazil, got everyone in the same room to talk about what they were working on that anyone made progress. “At [that] meeting at the Polytechnic School on academic networks, we discovered that there were also other groups in Brazil trying to establish connections with international academic networks.” Then, less than a year after that inaugural information-sharing session, three international connections went live in Brazil.

First was a dedicated line to the University of Maryland in September 1988, put together by the National Scientific Computing Laboratory. It ran at 9600 bps, fast enough to download a modern smartphone photo in 30 or 40 minutes.

The Fermilab connection came online one month later, this one at half the speed of the UMD line and encased in a submarine cable.

Finally, the connection to the University of California at Los Angeles began sending data to Brazil in May, 1989, orchestrated by a team at the University of Rio de Janeiro.

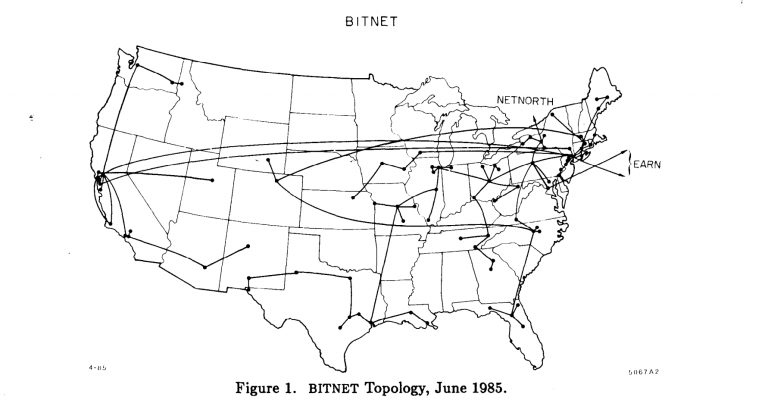

BITNET network diagram via Stanford University

Unlike AlterNex and its FidoNet connection, all three of these new lines operated on the BITNET network, which was, at the time, comprised of 1,400 academic and governmental entities across nearly 50 countries.

“BITNET had world-wide email; it had real-time, interactive chat, one-to-one or in ‘Relay’ chatrooms in places like CERN; it had world-wide remote file archives you could grab files from by issuing commands; it had world-wide ‘Listserv’ email discussion lists,” Dr. Mark Humphrys wrote in The Internet in the 1980s. “You could query if people were logged on across the world; it had disconnected ‘answering machines’; it had email to and from all other networks.” But it was not the Internet.

FidoNet, BITNET, and a handful of other mostly self-contained networks could “talk” to each other via dedicated gateways. They were still choke points, though. Everyone’s networks, both in Brazil and abroad, were a far cry from the monolithic, interconnected Internet that we have today.

The benefits of arriving late

Getschko recalls how the Fermilab connection to BITNET meant “an email took hours to arrive, sometimes a day, depending on the size of the dispatch queue. But it was great, because, compared to normal mail, there was no comparison—it was much better.” Still, without a national backbone or private point-to-point network, his team wouldn’t be able to connect directly to the National Scientific Computing Laboratory or the University of Rio de Janeiro. They had to route through a gateway in America before looping back to isolated networks in their own country. And even then, networks and most emails didn’t support sending Portuguese characters.

Obviously inefficient and inconvenient, the nascent Internet started to look like a far better option than BITNET and other networks. With its TCP/IP protocol, computers from any manufacturer could obtain a unique IP address, connect to the Internet, and send or receive data from anyone else on the Internet, as well as other networks, without relying on a small number of gatekeepers. Suddenly, the hora Brasil rollout was an advantage, with the switch being much harder on those who had invested more time and money on then-withering networks.

Demi Getschko (back row, furthest left) via Brazilian Network Information Center

When the Department of Energy decided to migrate to the Internet, Fermilab had no choice but to follow, which meant that Getschko’s team also needed to move. “I can’t remember the precise date, but it was in January 1991, when FAPESP shut down for vacation. Joseph Moussa was there and we received a tape with the program that would implement TCP/IP. Joseph installed the program, it worked and…the first Internet packets pinged [in Brazil].” He doesn’t remember what those first bits of data were. There was no way of knowing that the Internet would last any longer than BITNET.

Brazil’s other academic networks did not switch over to the Internet, according to a Fermilab report, which claimed that “Between 1991 and 1994, Brazil relied solely on a couple of wires that went through the Gulf of Mexico and up to Fermilab for all of its internet traffic.” Eventually, Embratel started offering Internet connections for personal use. But that, too, was limited.

As the only company with the infrastructure to connect to the web, “its approach was very centralizing: it set up a 0800 number that people could call, and everyone would have an e-mail account at @embratel.net.br,” according to Getschko. “Embratel would be the only Internet access point for Brazilians. There was an immediate reaction, because those on the academic network thought it was wrong for Embratel to be the ‘Brazilian Internet’.”

The government ended Embratel’s monopoly in May 1995 and Brazil showed up to the party in earnest.

It’s never too late to start something new

Demi Getschko and the FAPESP team were not the first ones to propose or finalize an international network connection. Their ANSP network was slower than others that went live at the same time. And yet neither setback stopped them from being the first group to successfully bring the Internet to their home country. No, they simply liked working with Fermilab and stuck with it despite others pursuing other avenues.

Starting a new website, blog, newsletter, anything online, really, feels like arriving at the party too late. Others have had a head start, or found time to post more aggressively than you. Daunting, sure, but not reasons to abandon all hope.

Email is not a zero-sum game, where an algorithm can bury your newsletter just because your content doesn’t “send the right signals.” Inboxes don’t discriminate. Maybe, arriving “late” means it’s easier to identify underserved audiences in a niche. Your subscribers might even have the appetite and space for two newsletters in the same niche. Succeeding is not predicated on being the last newsletter standing.

Michael Stanton, the one who organized the information-sharing session in 1987, didn’t work on the Fermilab-Internet connection. He worked in the same space, adjacent to Getschko, with his own networking projects, leaving behind his own legacy on Brazil’s Internet. “It took us three years. And they were very interesting years,” Stanton said during his induction speech into the Internet Hall of Fame.

Header image via Wikimedia commons by Santacruzense