The Turing Test and Our Fear of Humanoids

Welcome to the May issue of Hacker Chronicles!

Last month I reviewed 2001: A Space Odyssey with the sentient computer Hal. We are now going deeper on that subject, into human’s ability to detect artificial intelligence, robots, and cyborgs. And our fear of superhuman capabilities.

That will set us up nicely for upcoming newsletter issues reviewing my all-time favorite movie Blade Runner with its Voight-Kampff test. I also intend to review I, Robot by Isaac Asimov (book + movie), Ex Machina, and Terminator 1 & 2. So take the opportunity to (re)watch those movies now.

Regards, John Wilander

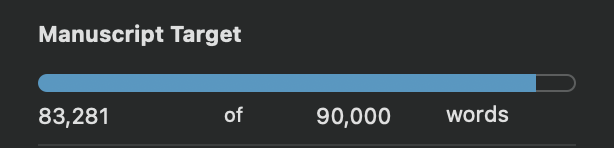

Writing Update

Had I just plowed on this last month, I would have been done with Draft 0 of my sequel to Identified. But there’s a particular subplot that needs special attention. I’m right now working on it in isolation, taking notes with pencil and paper, and thinking through exactly how it plays out. When a subplot is interspersed into the main plot, it can be hard to make sure it’s consistent and well-paced. That work made this months’ word count move slowly. But I need the subplot to be solid before I write the closing chapters.

This is where I am right now:

The Turing Test and Our Fear of Humanoids

Alan Turing devised his Turing test in 1950, and it’s about telling humans and machines apart. Or rather, when we can’t tell them apart, the machine is indistinguishable from a human and it can think.

In his original publication, he called it “the imitation game.” It’s funny how that became the title of the movie The Imitation Game which is about how Turing and his team hacked the Enigma, not the Turing test.

The Original Design of the Game

The imitation game involves three actors: The interrogator who is trying to figure out who of the other two is lying and who is telling the truth. The other two are a designated liar and a truth-teller.

Both the liar’s and the truth-teller’s job is to try to be identified as the truth-teller. The interrogator doesn’t get to see or hear the two others, but gets to ask them questions. The liar will lie and the truth-teller will be honest.

Turing exemplifies this with a lying man and a truth-telling woman, and the interrogator trying to tell who’s the man and who’s the woman. The man will do all he can to behave like a woman and also claim he’s a woman. The assumed distinction between two sexes makes the publication show its age.

Now replace the liar with a machine, and make it the interrogator’s task to tell which is human and which is the machine. The machine will do all it can to behave like a human and also claim it is human.

Ergo, the imitation game.

The Chinese Room – Critique of the Turing Test

Perhaps the most well-known critique of the Turing test came in 1980 and is called the Chinese room. It was presented by philosopher John Searle.

Searle argued that a machine locked away in a room that is able to behave intelligently isn’t necessarily intelligent. He posed the dichotomy between weak artificial intelligence and strong artificial intelligence.

A computer would pass the Turing Test if it that can write or speak Chinese well enough to convince a human Chinese speaker it is human too. But does the computer literally understand Chinese? Or is it just simulating the ability to understand Chinese? The former is strong AI and the latter is weak.

You can tell how fascinating that dichotomy is today with ChatGPT and its siblings. People like us are now pondering Turing and Searle’s ideas faced with a real subject under test 70+ and 40+ years later.

Are Today’s Chatbots Intelligent?

Casual participation in the conversation of today’s chatbots like ChatGPT has presented me with several angles that are fascinating to humans.

What does it mean to be intelligent? Maybe we are more like machines than some higher order being? You certainly come across dry assessments saying we’re just a complex cluster of connected neurons and the only reason why we think we’re intelligent is that we’re too dumb to tell that we’re predicable.

If machines become more intelligent than us, are they then more human than us? This question plays into our fear of being an insignificant speck in the course of the universe. But it also challenges the definition of being human. Is it really just about intelligence? What about emotion and spirit?

And what is creativity? Does something intelligent have to be creative? Especially generative AI has pushed the boundary of computer creativity. You often hear how human artists “steal” which means they get inspired by other pieces of art and craft. As an author, I can tell you that my initial doubts about the importance of reading when you want to write well have been put to shame. The most effective tool I’ve found to cure writer’s block is to read. Modern generative AI such as stable diffusion can feel very creative even though a big part of it is based on a human’s prompt.

I asked Stability AI’s system to generate me “A futuristic image of a hacker who saves the world in the face of adversarial computer systems.” It gave me this:

You may ask how an image-based Turing test would work. Well, it turns out this just happened: “AI-generated advertisements proved generally indistinguishable from human-made ads in a competition described as the first ad Turing test.” The source is a paywalled article in New Scientist.

ChatGPT’s Take On Creativity

I asked ChatGPT two questions on creativity.

Me: What is creativity?

ChatGPT: Creativity can be defined as the ability to generate original and valuable ideas or solutions to problems. It involves thinking outside the box, using imagination, and coming up with novel and unique approaches to challenges.

Creativity is not limited to artistic or aesthetic pursuits, but can also be applied in fields such as science, engineering, business, and education. It often involves a combination of divergent thinking (generating many possible solutions or ideas) and convergent thinking (narrowing down the options to the most feasible or effective).

Overall, creativity is an essential aspect of human cognition and is closely linked to innovation, problem-solving, and adaptability.

Me: Are you creative?

ChatGPT: As an AI language model, I am programmed to generate responses based on my training data and algorithms. While I am not capable of creativity in the same way that humans are, I can assist in the creative process by generating new and unique combinations of words and ideas based on the input I receive. I can also suggest new connections between concepts and offer alternative perspectives on problems. However, the originality and value of any output I generate ultimately depend on the quality and specificity of the input I receive from users.

Pretty solid.

CAPTCHA – The Everyday Turing Test

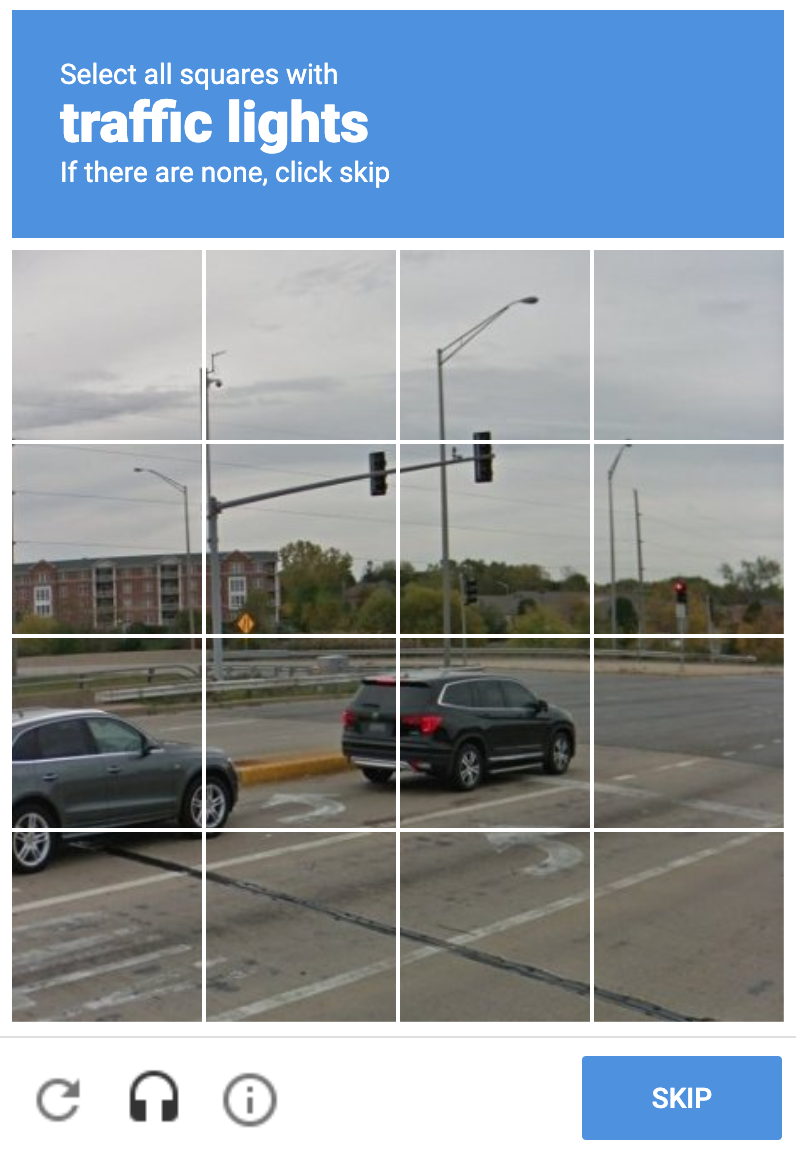

Completely Automated Public Turing test to tell Computers and Humans Apart, that’s what CAPTCHA stands for. You may know it as Google’s popular reCAPTCHA which started out as v1 with squiggly text, like this:

Then became object detection in photos, like this:

Being able to reliably tell human users and bots apart has turned out to be an immensely tough challenge, and competitive. The reason why CAPTCHAs keep getting harder and more annoying is that bots pass the easier ones, or it’s too cheap to pay humans in so called click farms to pass them on behalf of bots. Yeah, that’s humans working for bots who work for humans.

What you see in such CAPTCHAs is not all that’s going on. In the background, the Turing test software is checking how you move the mouse pointer, how quickly you click through the test, and whether it has other signals such as a purchase history on this website telling it you are likely a human.

Detecting bots this way is not about the philosophy of what intelligence is, but about fighting online fraud and scraping of data such as product prices.

Intelligent Machines in Fiction

Human-like computers, artifacts, or robots are frequent in fiction. Last month’s review of 2001: A Space Odyssey featured the computer Hal. But going back to the late 1930s you have the original I, Robot by Eando Binder, which inspired Isaac Asimov. Then in the 50s and 60s, for instance the manga android Astro Boy and Philip K. Dick’s classic _Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep? which Blade Runner is based on. Later C-3PO in Star Wars, KITT in Knight Rider, T-800 and T-1000 in Terminator 2: Judgement Day, and Ava in Ex Machina.

If you consider bronze and clay statues coming to life and talking, the tradition goes back to works of classical authors like Homer and Plato.

In some instances, finding the humanoid among us is key to the plot. In others, humans developing emotions for the machine is central to the story. Sometimes it’s even a plot twist where a character we thought was human turns out to be a machine. For all these flavors of fiction, the question of what it means to be human lies under it. And the Turing test is a famous, scientific attempt to answer that question.

Our Fear of Superhumans

I’d dare say most of us have a grandiose view of our own human species. Either as the peak of evolution or God’s finest creation. Challenging that with something superhuman or super intelligent cuts deep—suddenly we’d be inferior. We have an immensely dark history within our own species which touches upon this, with slavery and the Nazi’s Übermench vs Untermenchen as prime examples. Or the seemingly never-ending fight for women’s rights!

There’s a different challenge for authors and script writers. We’re human and limited in what superhuman things we can conjecture. Superheroes certainly do things we can’t, but they do things we can imagine. When you hear people’s reaction to what modern AI is capable of you realize that it’s often beyond their imagination. And that invokes just as much fear as wonder. Frankly, plain ol’ computer powers often fall in that unimaginable category.

Imitating Humans Is Just the Beginning

I write near-future fiction and I doubt my ability to predict a plausible future all the time. But I already use AI tools as an author. I expect to build a language model of my own writing to create a personal writing aid and I expect to release my novels as audio books with synthesized reading based on my own voice. That’s imitating a human in a very practical, productive way.

We are in an era where the public gets to try out AI for the first time. Our ability to just deal with that will inspire a lot of fiction in the coming years, I’m sure of it. But I’m also sure that once we have AI that can perfectly imitate humans and foil any Turing test we throw at it, that AI will be capable of so much more than that.

There is a beautiful way of getting that last point across. Imagine the Turing test with the computer telling the truth and the human lying. I.e. the human trying to be identified as a computer. It would be super easy for the interrogator to tell them apart—just ask them both a really hard math question and measure the speed at which they solve it.

Currently Reading

I’m still reading Four Battlegrounds: Power in the Age of Artificial Intelligence. With so much non-fiction reading this year, I’m really getting the urge to read fiction. For this summer, I’m considering The Three-Body Problem by Cixin Liu, an Agatha Christie crime novel, or The Trident Deception by Rick Campbell.

I have too many books waiting on the shelf. Sometimes I feel bad about that. But a friend who’s a librarian told me it’s good. You should always have enough books queued up so that when it’s time for a new one you get to browse and choose. I love looking at my bookcase and seeing a variety of books waiting for me.

US law requires me to provide you with a physical address: 6525 Crown Blvd #41471, San Jose, CA 95160