Review of Dead Space for the Unexpected

Welcome to the June issue of Hacker Chronicles!

This issue features a review of the short story Dead Space for the Unexpected.

Enjoy!

/John

Writing Update

I'm almost done working through all the feedback on Submerged from development editors and alpha readers. A couple of strong themes have emerged so taking action there will be a nobrainer. The toughest part will be cutting out a whole section that is not doing the job it's supposed to.

Then there are full-on opposing views. One alpha reader really loves certain aspects that another alpha reader says they don't enjoy much. The way out of that is to try to keep what's good but rework it to appeal to a broader audience. Sometimes that's just about cutting down a bit on details.

A tricky part will be to refine my foreshadowing and mystery. Readers want to feel like they know what's going on. At the same time I don't want to reveal things too early since learning what it is later has the payoff of "wow, I did not see that coming but it makes sense now." This is where I have not made up my mind yet. You can only frustrate your readers so much. I'm going to have to reveal a bit more, I think.

June Feature: Review of Dead Space for the Unexpected

You might recall from the April issue that Katherine R. Dollar recommended the short story Dead Space for the Unexpected by Geoff Ryman, published 1994.

One of the two reviews on Goodreads compares it to the cult movie Office Space which came out five years later. There are similarities.

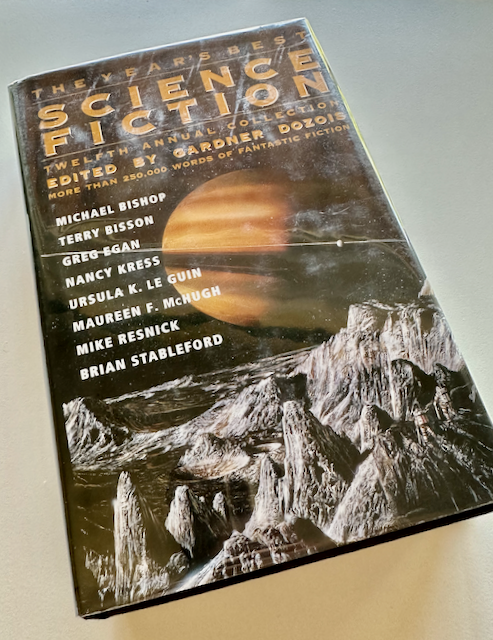

It was a little bit of a challenge to get my hands on this short story. It's not available new, neither electronic nor on paper. I had to get a used copy of The Year's Best Science Fiction: Twelfth Annual Collection from the 90s.

Opening Scene: The Firing of Simon

The story's protagonist Jonathan is a manager who is about to fire Simon, an employee in his 50s. Jonathan needs to handle the situation really well since he'll be scored on it in a computer system and he and his team are currentluy not doing well score-wise.

Data points that contribute to the score are collected in several ways. Jonathan wears contact lenses that track his eye movement, his shirt has a checkered pattern that enables surveillance cameras to record his breathing pattern, and he wears a watch strap that measures his galvanic skin resistance.

Monitoring of ones body is voluntary but you have to to get the scores you want.

The firing of Simon is set for first thing in the morning and it goes poorly. Jonathan is not able to empathize or follow the steps in his training, simply because Simon reacts in an unpredictable way to his firing. Simon even refuses to pick up the termination of employment letter at first.

"You forget," said Simon his blue eyes gray and flinty, "I used to work in Accounts." He picked up the letter, paused, and wiped his finger on it. Then he left the room.

Jonathan struggles to contain his anger. He's angry at Simon who doesn't accept that his poor performance means he has to go. And he's angry about his own performance and the bad score he's going to get.

Thoughts

A lot of this kind of tracking is already upon us in real life, albeit mostly for personal data collection. Worrying about your performance rating on a daily basis hasn't reached work life in my experience but I think a lot of work is being measured more.

Stack ranking is a performance management practice that developed in the 1980s and is still in use today. Under such a scheme, a certain percentage of the work force should get low ratings and be fired. This means that you constantly have to be in the top e.g. 90% to keep your job.

When you combine stack ranking with detailed monitoring of workers you get the kind of dystopia Ryman is describing.

Jonathan's Score Drops

Jonathan attends a couple of lousy meetings as his morning progresses, including with his nemesis Sally. Once back in his office he frets over the bad start of day.

He reviews the surveillance video of when he fired Simon. The computer system has concluded that Simon is highly likely to plan sabotage at the office given his flesh tone, oxygen use, body language, uncharacteristic verbals, and atypical eye movements.

Jonathan is furious that the system didn't warn him of this right after the conversation with Simon. Who knows what Simon has been scheming since then? The computer response is that he has configured it to hold all such notifications until his calendar shows "Dead space for the unexpected."

He asks the system what Simon has been up to since they talked. The system is unable to provide details.

Jonathan notes that his own performance score drops from 7.2 to a dismal 5.2.

He can't access Simon's employee files because employment has been terminated. But he also cannot access the ex-employee files.

Another direct named George comes by and Jonathan asks if he's seen Simon. George says Simon looks really content – like a prince.

They realize that what Simon meant with having worked in Accounts is that he has access to the Accounts system and can change others' score. Not only can – he has.

Thoughts

Simon being disgruntled isn't a surprise but some kind of central access to people's profiles and scores is. Nowadays it's common practice to shut off all computer system access before even notifying the employee of termination to limit what damage they can do. The main risk in such scenarios is likely information theft.

Opaque data collection that produces a score without scrutiny and transparency is a recipe for bad outcomes given that software always has bugs and security vulnerabilities. I.e. there can be errors in the data and there can be manipulation of the data.

The insurance industry has been accused of having this problem, with closed statistical models deciding whether a person should be offered insurance or not. March this year, The New York Times (paywalled) broke the news that General Motors allegedly was sharing data collected in vehicles with insurance companies:

Mr. Dahl, 65, was surprised in 2022 when the cost of his car insurance jumped by 21 percent. Quotes from other insurance companies were also high. One insurance agent told him his LexisNexis report was a factor.

LexisNexis is a New York-based global data broker with a "Risk Solutions" division that caters to the auto insurance industry and has traditionally kept tabs on car accidents and tickets. Upon Mr. Dahl's request, LexisNexis sent him a 258-page "consumer disclosure report,"" which it must provide per the Fair Credit Reporting Act.

What it contained stunned him: more than 130 pages detailing each time he or his wife had driven the Bolt over the previous six months. It included the dates of 640 trips, their start and end times, the distance driven and an accounting of any speeding, hard braking or sharp accelerations. The only thing it didn't have is where they had driven the car.

Access to Accounts it Too Spicy For Comfort

Back to the short story. Jonathan concludes that Simon must have gotten access to some kind of main password when working in the Accounts department. Even so, his access seems to allow for data manipulation that should not be possible.

"This is different, it really lays open the whole network. I think only the Chairman has it, maybe Head of Accounts. You get hold of that you can change any information you like and then ice it, so it can never be changed. Change it invisibly I mean."

"Great for when the Auditors call."

"I expect so."

Jonathan brings in Simon and questions him. Simon laments how he poured twenty years into this company only to be sacked because he got old. Jonathan says it's not age, it's performance. Simon admits having lowered his coworkers' scores.

Once the hack is resolved, Jonathan is pleased to note that he got a score of 10 for his actions.

Thoughts

It's highly believable that a company would put the lid on an incident where an employee gets über access that could possibly be used to doctor auditing logs. Internal hacker attacks in general may be deemed embarrassing and revealing. In this case the legitimacy of the whole scoring system is at risk.

Bigger picture, this touches upon the risk of relying on computer systems without human gut checks. And even with humans involved, those humans can be malicious or disgruntled. It's impossible to have anything more than spot checks at the scale and speed our current day computer systems. To what extent am I already judged by statistical models processing personal data? Probably in the case of insurance.

Currently Reading

I finished reading Open Source by Anna L. Davis. That means I'll be interviewing Anna about it soon. Stay tuned for that!

I'm focused on Four Battlegrounds: Power in the Age of Artificial Intelligence because I want to move on to White House Warriors: How the National Security Council Transformed the American Way of War.