Gutenberg and The Digital Horizon

Welcome to the March issue of Hacker Chronicles!

My upcoming novel Submerged has been typeset, and I recently visited the Gutenberg Museum in Germany. That inspired me to write about a little known concept, or term, that had a profound impact on my thinking when I learned about it in the early 2000s – The Digital Horizon.

Enjoy!

/John

Writing Update

I'm on the third draft of the cover for Submerged. Writing the blurb for the backside was not easy because I don't like spoilers myself. But I realized it wasn't possible to write it spoiler-free. So my advice for you is to not read the backside if you've already decided you're going to read the book.

I'll reveal the cover once it's ready. Meanwhile, here's the title page to the right of the copyright page:

The title page.

Once I was through the copyedit of Submerged, we got to formatting and I could pick a font. I'm happy to tell you I went with the beautiful Sabon typeface, designed by Jan Tschichold (1902–1974) and part of "typographic modernism" in the 20th century:

The Sabon typeface.

I hope to finish the review of the formatting today, including some changes to make maps work well in gray scale.

The audiobook recording has started. Kristin Price emailed me yesterday with some final suggestions. My writing contains technical details and she and I always have to figure out a way how to read that aloud without boring the listener (imagine listening to a binary string like 0101110100100100) but still convey all necessary details. It's difficult, and in the back of my mind is a desire to write in a more audio-friendly way.

March Feature: Gutenberg and The Digital Horizon

Right around the time of me picking the Sabon typeface, I was visiting Mainz in Germany and went to the Gutenberg Museum.

Gutenberg and the Invention of the Printing Press

I recently listened to a great lecture series called Turning Points in Modern History Audible link, and of course, Johannes Gutenberg's movable-type printing press was one of those turning points.

Before Gutenberg, books were hand-written and thus rare and expensive. Chances for regular people to read were scarce, if they could even read at all.

Written story telling and literacy developed differently in various parts of the world. But the way we think of literature today was very much influenced by the printing press, the move to write in a common language such as English instead of Latin, and the rise of mainstream literature such as The Canterbury Tales.

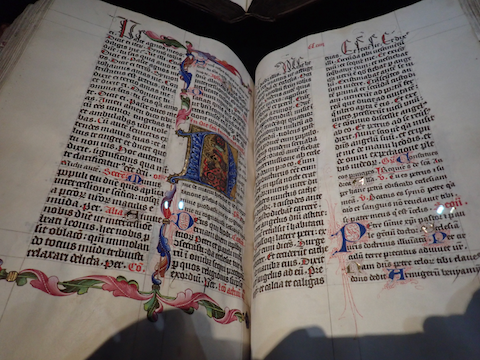

Gutenberg was however fully focused on religious books and spent the early days printing bibles. His 42-line Bible in Latin is believed to have been printed between 1452 and 1454.

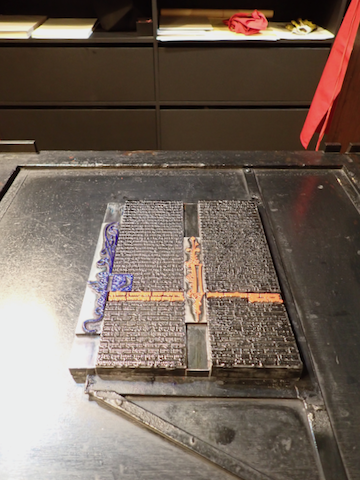

To see one of those bibles is profound. They are on display in the museum's Treasury. Here are a couple of my photos:

The beautiful Zum Römischen Kaiser building where the Gutenberg Museum normally resides.

Entrance to the temporary location of the Gutenberg Museum.

One of the original Gutenberg Bibles on display.

A working replica of Gutenberg's printing press and movable types.

The Spread of Printing

Interestingly, Gutenberg tried to maintain a monopoly on his invention but lost a lawsuit against his investor Johann Fust. Suddenly there were two printing shops in Mainz and the secret of the technology was out.

Printing spread in Western Europe during the following two decades. Cologne 1466, Rome 1467, Venice 1469, Paris 1470, Buda (part of Budapest) 1473, Kraków 1473, and London 1477.

It's estimated that by 1500, Western Europe had printed 8 million books! Sure, 50 years was well over the average life expectancy during that time, but what a development.

Longevity of the Written and Printed Word

Not only was printing an incredible invention, but equally important was the development of paper. The earliest known traces of paper are from the 2nd century BCE in China. From there it spread to the Islamic world via two Chinese prisoners, and Muslims eventually brought paper making to the Indian subcontinent and to Europe.

The fact that paper and ink have stood the test of centuries is incredible. Thoughts, stories, records, and accounts have been preserved verbatim. It took Jane Austen sixteen years from first draft to a printed first edition of Pride and Prejudice, but I can read it today just the way she wrote it.

Title page of the first edition of Pride and Prejudice 1813.

The Digital Horizon

The Digital Horizon – a term and concept that had a profound impact on young me in the late 1990s or early 2000s.

Books, music, and information that don't get digitized, end up beyond The Digital Horizon and die. Die in the sense of no one looking them up anymore or even knowing they exist. Eventually, the last physical copy will be lost and the artifact truly dies. Researchers won't consider it in their work, stories won't be read, and the longevity of ink and paper is disrupted in practice.

I tried looking up the reference by emailing fellow Swede Lars Aronsson whom I thought coined it. He doesn't recall it, but pulled in two others. They in turn pulled in a fourth person. The hunt continues. These are Swedish pioneers in the digital age, championing free and open access to information, most recently with OpenStreetMap.

Project Gutenberg – Addressing The Digital Horizon

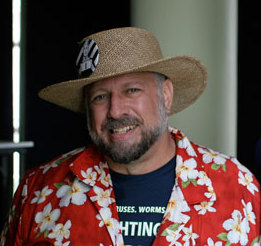

The American inventor of the ebook Michael S. Hart founded Project Gutenberg in 1971. It's a volunteer effort to digitize and archive cultural works and encourage the creation and distribution of ebooks. Project Gutenberg is the oldest digital library.

Photo of Michael S. Hart.

Digitizing and thinking of ebooks in 1971. Talk about foresight.

Aforementioned Lars Aronsson founded a Project Runeberg in 1992 to publish free electronic versions of books significant to the culture and history of the Nordic countries. As soon as a Nordic literary piece is outside copyright, they digitize it. It was directly inspired by Project Gutenberg.

Nowadays there are many sibling projects, such as Project Gutenberg of the Philippines, Project Gutenberg of Taiwan, and Project Gutenberg Australia.

Longevity of Digital Information

Project Gutenberg and siblings are helping humankind digitize and new books are published in digital formats from the get-go. Does that mean we're good for the future? Unfortunately not.

Digital formats and the software to turn them into pixels we can read as text age and die too.

Encoding and Data Formats

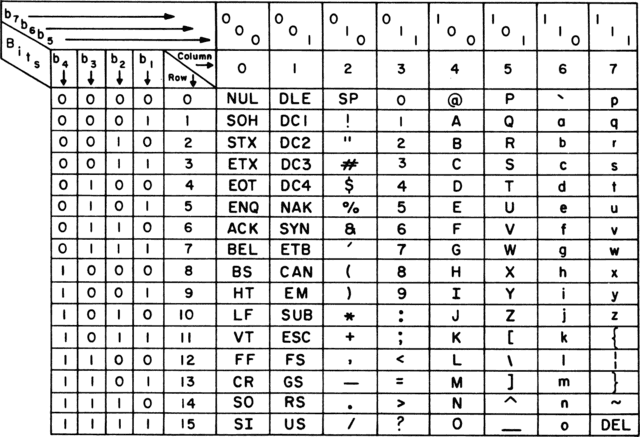

Project Gutenberg release works in plain text, HTML, PDF, EPUB, MOBI, and Plucker. From what I can tell, the plain text started out as 7-bit US-ASCII which originates from 1961.

The US-ASCII table showing the 7-bit encoding.

From there, they've expanded to 8-bit ISO/IEC 8859-1 which has its roots in the early 1980s. And nowadays they use modern UTF-8.

Mobi as an ebook format is all but gone. PDF has evolved significantly since its inception in 1992 and was based on the PostScript language from the early 1980s.

Storage

On top of the challenge of text encoding and data formats, you have the challenge of storage medium and its longevity. From magnetic tapes to floppy discs to hard drives and laser discs to today's SSDs.

I wrote a whole newsletter issue on this topic called Long-term storage of data in January 2023. It covers storage media, data protection, data correctness, and nice examples of where it matters in fiction such as Johnny Mnemonic and Minority Report.

Final Thoughts

The digital age, or information age, has truly revolutionized how we publish and access information, including fiction. That change is surely of the same magnitude as Gutenberg's printing press. With it, with gotten the challenge of The Digital Horizon.

A profound difference between the printed word and the digital word is that the latter can always change. You see that in how new sites iterate on headlines, or even unpublish things. I touch upon this in a tense moment in my upcoming novel Submerged. I think you'll like it.

Currently Reading

I finished reading The Demon Lord by Peter Morwood. Now I'm reading two books in parallel – Kill Decision by fellow hacker fiction author Daniel Suarez, and Det förlorade paradiset by Prof. Sara Kristoffersson. The latter is non-fiction about the rise and gradual fall of the Swedish retailers' cooperative.